Translation Journey: Unveiling the Linguistic Evolution of the Bible through its Titles and Historical Transformations

Names

The English word for the Bible comes from the Greek biblos and biblion and means “book” and “little books.”[i] The Bible is also called “the Scripture,” “holy writings,” “sacred writings,” “the oracles of God,” and most descriptively, “the Word of God.”[ii]

The Old Testament was almost entirely written in Hebrew, with a few short elements (Daniel and Ezra) written in Aramaic.[iii] The first five books, called “the books of Moses” and the Torah (also called the Pentateuch or Chumash, meaning five), were translated from Hebrew into Aramaic (Targums). By the middle of the 3rd century B.C., the Hebrew canon was translated into Greek and later into Latin (Septuagint). The spread of Christianity later necessitated the translation of the entire Bible into Coptic, Ethiopian, Gothic, and Latin.[iv]

In the 6th century B.C., Hebrew scholars during the Babylonian Exile gradually replaced the Paleo Hebrew letters of the Old Testament with an Aramaic text (Masoretic text). The fonts were likely adopted from the Ashurith or Assyrian language. The Paleo and Aramaic alphabets are similar, so the meaning of the Hebrew text did not change. During the Second Temple period, the Aramaic letters developed the “square shape” of the modern Hebrew Alphabet we see today.

Jerome’s Latin Vulgate was the basis for translations of the Old and New Testament into Syriac, Arabic, Spanish, and many other languages, including English. The Vulgate is a late 4th century Latin translation of the Bible. The first complete English-language version of the Bible dated from A.D. 1382 and was credited to John Wycliffe. This and other English translations, including the works of William Tyndale (A.D. 1525 to 1535), culminated in the King James Version (A.D. 1611; known in England as the “authorized version”). Considered a near “word for word” translation utilizing synonyms instead of strict literalism, the King James Bible has been the predominant version used by English-speaking Protestant denominations for more than two-hundred seventy years.

Through this myriad of translations, nearly all the names, people, and cities in the Bible have been anglicized. For example, the name “Jesus” is related to the Hebrew form Joshua (Yehoshua—יְהוֹשֻׁעַ). This early Biblical Hebrew name underwent a shortening into the later name of Yeshua (יֵשׁוּעַ). The Septuagint transliterated Yeshua from Hebrew into Koine Greek in the second or third century B.C., resulting in Ἰησοῦς (Iēsous). We will use the anglicized Biblical names as much as possible for clarity. The original language or transliteration will, on occasion, be accompanied in parentheses.

As of the late twentieth century, the entire Bible has been translated and published in more than thirteen hundred languages. The King James Bible has since been updated as the Revised Standard Version (A.D. 1946–52), the New English Bible (A.D. 1961–70), the New International Version (A.D. 1978), the New Revised Standard Version, and the Revised English Bible (A.D. 1989), and the English Standard Version (A.D. 2001).

Divisions

The Bible is divided into the “Old Testament” and the “New Testament.” The word “testament” was initially translated as “covenant,” signifying that each book represents a different covenant—one old about the Law of Moses, and the other new on the “new covenant” that Christ administered. Recognizing there are multiple covenants listed in the Old Testament, including the promise of the New Covenant, I prefer to see both volumes as one continuing story of God’s revelation of Himself to humanity through the nation of Israel. However, I will refer to each as they are commonly used for clarity.

The thirty-nine books of the Old Testament are grouped into one of three divisions: The (five) Books of Moses (Torah), the Writings (Ketuvim), and the Prophets (Nevi’im). In Judaism, the Torah provides the foundation for all Jewish Law, called the Law of Moses (Pentateuch/Chumash) and Halacha. The word “Torah” comes from the Hebrew hora’ah and means “teaching” or “instruction,” as the Lord commanded the Israelites, “And teach them to your children and your grandchildren, They shall teach Jacob Your judgments, And Israel Your law” (Deuteronomy 4:10 & 33:10, NKJV).[v]

The Writings include poetic books, such as the Psalms, historical texts, and scrolls (Megillot), initially kept separate, stand-alone documents from the Bible (Tanach). Tanach is an acronym for Torah (Five Books of Moses), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). They are sorted by Major and Minor based on the length of writing. Lastly, the Prophets include both the former and latter depending on the period.

Jesus referred to all three of these divisions in saying, “These are the words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things must be fulfilled which were written in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms concerning Me” (Luke 24:44).[vi] While the Torah is considered a work of law and guide for life, the Prophets inspired the Jewish people to repentance. And the writings were to provide Israel with a perspective on their history and guide them into a proper philosophical outlook on life.

The twenty-seven books of the New Testament are grouped into one of four divisions: The Biographical (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), also referred to as “the Gospels,” Historical (Acts), Pedagogical, also called “epistles,” and Prophetic (Revelation). The books of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are called “the synoptic Gospels,” as it is believed they were written from the same source, likely Aramaic, and Greek manuscripts.

Chapters and Verses

In its original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek languages, the Bible was not organized with chapters and verses. The New Testament was first published with divisions in A.D. 1551, and the entire Geneva Bible was divided into verses in A.D. 1560. These divisions were infused for convenience of reference and are not considered to be inspired. Some divisions have created confusion by segmenting subject material. Therefore, when studying scripture, it is acceptable to reference these divisions, best to ignore them regarding translation and interpretation.

Writers

While penned by many, the Bible expresses “one” ultimate author—God Himself. As I like to say, the Bible reveals God’s one continuous story of His unfolding relationship with the creation through the nation of Israel. It is practically impossible to understand the New Testament without a firm knowledge of the Old. It is also important to remember that nearly the entirety of scripture, except the epistles written by Paul to the churches in Asia Minor, was written by at least forty Hebrew/Israelite men to the nation of Israel over more than fifteen hundred years.[vii] Thus, we need to see it from their perspective when reading scripture.

Paul said, “What advantage then has the Jew, or what is the profit of circumcision? Much in every way! Chiefly because to them were committed the oracles of God” (Romans 3:1-2). An oracle is merely a person of priestly authority that God uses to declare His prophecies concerning the future. These prophecies speak to the salvation and restoration of Israel and her salvific relationship with the Gentiles. In other words, the salvation of all humanity is directly tied to Israel, and the Bible is the written assurance that God has provided to Israel, declaring His promise to save all people through her—chiefly, a Rod from the stem of Jesse, and a Branch who is Christ.[viii] Jesus said, “We know what we worship, for salvation is of the Jews” (John 4:22).

While the Bible was written mainly to Israel, the Gentiles are not precluded from its universal message. Most importantly, in Christ, they are now part of God’s “New and Everlasting Covenant” prophesied to all people as the Lord declared, “Ho! Everyone who thirsts, Come to the waters… And I will make an everlasting covenant with you—The sure mercies of David… And nations who do not know you shall run to you, Because of the Lord your God, And the Holy One of Israel” (Isaiah 55:1-5).

Canons

The word “canon” comes from the Greek kanon, and it means “a measuring rod/rule” and signifies a rule and standard. Therefore, the canon of the Bible only consists of the books considered worthy to be incorporated into the Holy Scriptures. It is essential to know that the Jewish canon of the Old Testament contains fewer books (twenty-four verses thirty-nine) and is ordered slightly differently from the Protestant Christian one. Also, some of the verse numberings are different. However, the overall content is relatively the same. For this study and consistency with Christian writings, we will reference the Protestant canon of scripture, its book, and verse numbering.

The canonization of the Bible was completed over centuries. It incorporated only those writings that proved necessary for deepening of faith and worship, inspiration, and edification. It was not indoctrinated by rabbinic or church decree, nor by any ecclesiastical council, but by testing each book and its intrinsic value and reception by the worshiping communities.[ix] These canonized books possess and exercise divine authority before any pronouncement of man. We only confirm and agree with what God has already established.[x]

As mentioned previously, the canon of the Old Testament includes three divisions, the first being the five books of Moses (Pentateuch/Chumash). These are also called “the book of the Law” and “the book of the covenant.” The remaining two divisions are the prophets and the writings. Collectively, all three divisions are called the “Old Testament” and the Mikra/Tanach.” The Hebrew canon is somewhat fluid up to the early 2nd century.[xi] George L. Robinson has suggested that the Pentateuch was finally canonized at the time of Ezra (B.C. 444), the prophets around B.C. 200, and the writings around B.C. 100.[xii] Other scholars hold to two periods of canonization being complete around B.C. 400.[xiii]

What is important to remember is that the entire Jewish canon of the Old Testament was complete during the time of Jesus, and He referred to them as “the scriptures.” Further evidence is included in the writings of the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus. He said the Jews only have “twenty-two books, which contain the records of all the past times, which we justly believe to be divine…”[xiv]

Although not canonized in scripture, a select group of rabbis (tannaim) assembled a post-biblical collection of oral (unwritten) laws, the Mishnah. The Mishnah supplements the written laws found in the Pentateuch. For about two hundred years, the codification of a part of the oral law was given its final form in the 3rd century A.D.[xv] The codified Mishnah was expanded to include the Gemara (A.D. 200-500). Rabbinic commentaries surrounding the Mishnah, Gemara, and the written laws were compiled in the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds.

Jewish traditions (chalaka/upsherin) evolved from the Talmud over many centuries. After the Babylonian exile, synagogues were established to perpetuate the essence of Judaism, teaching the whole law, written and oral, to the next generation of rabbinic scholars (amoraim). Jesus referred to these rabbinic traditions, saying, “Why do you also transgress the commandment of God because of your tradition? Thus you have made the commandment of God of no effect by your tradition” (Matthew 15:3 & 6). Bear in mind that Jesus was not against traditions. He was against those practices that misconstrued God’s commandments.

There is controversy surrounding the origins and credibility of the “oral laws.” We will treat these as “uninspired” and reference canonized scripture to validate our theology. However, there is a degree of wisdom and insight in the rabbinic commentaries that we will use, on occasion, to help us better understand the Bible from a Hebraic perspective.

The Roman Catholic Church canonized fourteen additional books with the Old Testament, called the Apocrypha. Orthodox Bibles incorporate some of these Apocryphal books differently, called the “longer canon.”[xvi] The word Apocrypha means “hidden” or “concealed.” The Septuagint (LXX) translation of the Old Testament into Greek (B.C. 280-180) incorporates the apocryphal books. Jerome included them in his 4th century Latin translation of the Old Testament, called “the Vulgate.” These books are not part of the Jewish canon. The reformers were responsible for eliminating them from the Protestant Bible as they contained passages inconsistent with Protestant doctrine.

The canon of the twenty-seven books of the New Testament is much easier to trace. The New Testament was primarily written during the last half of the 1st century A.D. The newly emerging group of Jesus followers were predominantly Jewish, and they already possessed a solid grasp of Old Testament prophecy. But additional importance was placed on the words of Jesus, most of which are recorded in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. These are presented as eyewitness accounts of Jesus, affirming His Messiahship.[xvii] On the other hand, the epistles of Paul were written primarily to meet the specific needs of the local churches. There is also a strong suggestion of an early canon of New Testament scriptures recognized with the Old.

During the early years of the 2nd century A.D., the church fathers quoted profusely from books that would become the canon of the New Testament.[xviii] By the end of the 2nd century, all but seven of the twenty-seven books of the New Testament were recognized as canonical. Within twenty-five years of the Diocletian persecution, Constantine, the new emperor of Rome, had embraced Christianity. Therefore, it became necessary to decide which books would be included.

There were many books at this time that were considered heretical or false. The writings were eventually separated into two groups: Pseudepigrapha (spurious and heretical) and Apocrypha (not to be confused with apocryphal books of the Old Testament). The spurious and heretical books of the Pseudepigrapha were never recognized by any council or quoted by the church fathers. The New Testament apocryphal books were highly esteemed by at least one church father.[xix]

When completing the canon, five principles were used to test every writing: Apostolicity (was the book written by an apostle or one who was closely associated), spiritual content (was it read in the churches), doctrinal soundness (void of heresies), usage (universally recognized by the churches), and held evidence of Divine inspiration.[xx]

The books ultimately listed as the New Testament Apocrypha were those held in high esteem by the church fathers. At the third council of Carthage (A.D. 397), the western Christian churches agreed on the final form of the New Testament canon. Thus, by the end of the 4th century, all twenty-seven books of the New Testament had been received. Not one has been added or removed since then.[xxi]

Translations

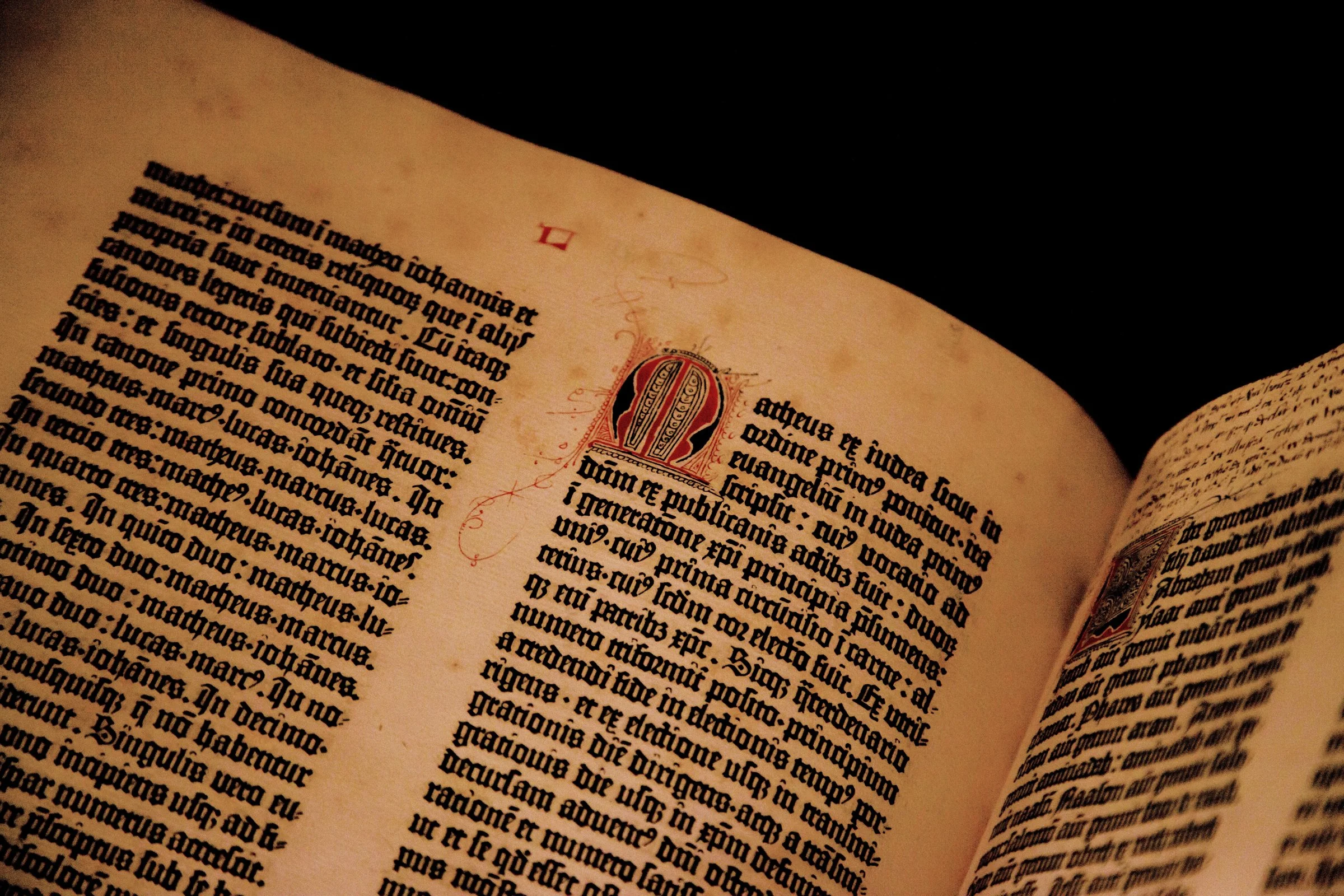

The narrative of scripture begins with the original manuscripts, also called “autographs.” These original texts were scribed and penned by men moved upon by the Holy Spirit.[xxii] The word “manuscript” is restricted to copies of the Bible made in the same language initially written. There must be at least ten to twenty comparably equal texts for a writing to be genuine. By the time the Bible was printed (A.D. 1455), over two thousand manuscripts were in existence. Presently, there are around forty-five thousand manuscripts of the New Testament. These high numbers prove the authenticity of the Bible.

Archeology has proven that written languages predate the time of Moses. Sumerian writings date to around B.C. 4,000, and Egyptian and Babylonian writings are even older. Materials included stone and clay tablets, wood, leather, papyrus, and later, vellum and parchment.

The first codex book form manuscripts have been dated to the 1st century A.D. The Essenes who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls used burnt lamb bones and oil. Writing instruments included chisels, metal or wood styluses, and pens made from hollow stalks or reeds.

The Bible was originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. Aramaic is mostly a lost language but still spoken by a few Christians in Syria. The sages consider Aramaic a special and unique language, and Rabbi Moses Isserlis said that Aramaic has a semi-holiness that dates to Mount Sinai. As beautiful and poetic as this language is, the rabbis only call Hebrew “the Holy Tongue.”[xxiii]

They assert that Biblical Hebrew is God's language used in the creation and is the foundation for all that exists. And they believe it emanates from His four-letter name (the Tetragrammaton), sustaining the creation and continuing to bring it into being out of nothingness (Latin ex nihilo) and affirming His Oneness with all created things. Modern Hebrew and Greek are different from their Biblical counterparts (e.g., koine Greek) but are still spoken.

New Testament manuscripts are classified as uncials (Latin uncia, meaning inch) older manuscripts written in large Roman capital letters on fine vellum. And cursives or running hand, written on vellum and papyri dating from the 10th to 15th centuries A.D. About thirty incomplete manuscripts have been discovered on broken pieces of pottery, called ostraca.

Significant manuscripts are the Sinaitic (Codex Aleph), Vaticanus (Codex B), Alexandria (Codex A), Ephraem (Codex C), and Beza (Codex D). The last group is Lectionaries, selected scripture passages designed to be read in public services. Some were uncials, and others cursive.

Almost all thirty-nine books of the Old Testament were written in Hebrew. One word named in Genesis, and portions of Jeremiah, Daniel, and Ezra were written in Aramaic.[xxiv] While written in Greek, the New Testament contains several translated or transliterated Aramaic words.[xxv]

Versions

A “version” is a translation from the original manuscript language into another language. We will discuss some of the most notable ones, beginning with the Septuagint, meaning “seventy,” version LXX. It is a translation of the Old Testament Hebrew into Greek (B.C. 200-180), and it is believed the translation was done by Alexandrian Jews (Alexandria, Egypt). Commonly used in New Testament times, it contains thirty-nine books of the Old Testament, including the Pentateuch and the fourteen books of the Apocrypha.

The Samaritan Bible is not a translation, but a Hebrew Pentateuch written in Samaritan letters (B.C. 430), a form of the Hebrew text. The Cureton Syriac is a 5th-century copy of the Gospels. Syriac was the principal langue of the Assyrian and Mesopotamian regions. The Sinaitic Syriac was discovered at Saint Catherin’s Monastery at Mount Sinai (4th or 5th century A.D). The Peshitta, meaning “simple” or “common,” is a Syriac Vulgate and Authorized Version of the Church of the East. It has been in use since the 5th century A.D. It contains all the New Testament, excepting 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and Revelation.

The first English Bible was translated from Latin. The Old Latin translation dates to around A.D. 150. The Latin Vulgate (meaning “common” or “current”), also recognized as the Jerome Vulgate, is the prominent version of the Bible in Latin. It corrects many of the errors found in the Old Latin version. The New Testament dates from A.D. 382-383, and Old Testament from A.D. 390-405. For more than one thousand years, every translation of scripture in Western Europe has been based on this work. It was made the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church and was the first book printed from moveable type (A.D. 1455). In contrast, the Protestant Bible was translated from the original Greek.

The Scriptures in English

The English Bible dates to the 7th century A.D. when an uneducated laborer named Caedmon arranged stories from the Bible in verse form. In A.D. 705, Aldhelm translated the Psalms into English, and venerable Bede completed the Gospel of John in A.D. 735. King Alfred translated the ten commandments, other laws of the Old Testament, the Psalms, and the Gospel of John in the late 9th century A.D. Aelfric, the Archbishop of Canterbury, translated the Gospels and first seven books of the Old Testament around A.D. 1000.

John Wycliff, an Oxford teacher, and scholar, with the help of his students, translated the entire Bible into English from the Latin Vulgate. The work was completed in A.D. 1382. A revision was done by John Purvey in A.D. 1388 and remained in use until the 16th century A.D. In A.D. 1516, Erasmus, a monk-scholar, first printed the New Testament in Greek. After fleeing to Hamburg, Germany, because of opposition from the Roman Catholic Church, William Tyndale finished the translation of the Bible into English.

In A.D. 1450, Johann Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, invented the printing press with moveable type. His first published book was the Latin Vulgate (Mazarin Bible) in A.D. 1455. Tyndale later printed his English translation of the New Testament in A.D. 1525. Tyndale continued translating the Bible into English until he died in A.D. 1534. He completed the Pentateuch in A.D. 1530, Jonah in A.D. 1531, and a revision of Genesis in A.D. 1534. His dying words were, “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” The King James, Authorized Versions is the fifth revision of Tyndale’s work.

Other English Bibles include the Coverdale Bible, the work of Miles Coverdale, completed in A.D. 1535. The Matthew’s Bible, the work of John Rogers, was completed in A.D. 1537. The Great Bible, a revision of the Matthew’s Bible, was published in A.D. 1539. The Geneva Bible, the first Bible with verses, was published in A.D. 1560. The Bishop’s Bible, the work of Bishop Parker and others, was published in A.D. 1568. The Rheims-Douai Bible, the first Roman Catholic edition of the English Bible, final publication in A.D. 1610. The King James Bible, published in A.D. 1610. About forty-eight Greek and Hebrew scholars were selected to complete the work. It has remained the most popular and widely accepted version of the Bible for more than four hundred years.

Recent English translations of the Bible include: The English Revised Edition, completed in A.D. 1885, the American Standard Version published in A.D. 1901, the Revised Standard Version completed in A.D. 1952, and the New International Version completed in A.D. 1978. During the past several decades, there has been a flood of new translations, some purposing to be literal renderings of the original text, while others are paraphrases into modern English. It is reassuring to know through all these translations, the substantial integrity of the veritable word of God remains intact.[xxvi]

[i] Luke 4:17.

[ii] Matthew 22:29. Mark 7:13, 12:10 & 24, 15:28. Luke 4:21, 24:27. John 2:22, 5:39, 7:38, 10:35. Acts 17:11. Romans 1:2, 3:2, 4:3, 10:17. 1 Corinthians 15:3-4. 2 Corinthians 2:17. Galatians 4:30. 2 Peter 1:20, 3:16. 2 Timothy 3:15. 1 Thessalonians 2:13. Hebrews 4:12.

[iii] Biblical Translation. Encyclopedia Britannica.

[iv] Duffield, Guy P. and Van Cleave, Nathaniel M. Foundations of Pentecostal Theology. Foursquare Media. 1910.

[v] All Scripture quotations are taken from the New King James Bible (NKJV) unless otherwise noted, Thomas Nelson Inc., 1982.

[vi] Matthew 5:17, 11:13. Acts 13:15. John 10:34, 12:34, 15:25. 1 Corinthians 14:21.

[vii] There is theological debate surrounding Luke and whether he was a Gentile. It is most probable that Luke was a Jew given that Paul brought him into the Temple, rather than Trophimus who we know was a Gentile. Temple Laws would have required Luke to be severely punished for violation of these Laws. Non-Jews were allowed to enter the outer court, also called the Court of the Gentiles, but were forbidden to go any farther. The inner courtyards were only for Israelites and were enclosed by a balustrade. The entrances were posted in both Greek and Latin, warning foreigners and uncircumcised persons that crossing these was punishable by death.

[viii] Isaiah 11:1.

[ix] Selby, Donald J. and West, James King. Introduction to the Bible. The Macmillan Company, 1971, 2.

[x] Exodus 24:3-4. Deuteronomy 31:9-11, 24-26. Joshua 24:26. 1 Samuel 10:25. Jeremiah 36:2. Daniel 9:2. Nehemiah 8:1-8. 2 Kings 22:8, 23:2.

[xi] Nivi’im: Old Testament. Encyclopedia Britannica.

[xii] Robinson, George L. International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1943, I, 554-563.

[xiii] Geisler, Norman I. and Nix, William E. From God to Us—How We got Our Bible. Moody Press, 1974, 85.

[xiv] The Life and Works of Flavius Josephus, trans. William Whiston. The John C. Winston Company, 1936, 861-862.

[xv] Mishna: Jewish Laws. Encyclopedia Britannica.

[xvi] Canon of Scripture. Orthodox Church in America (oca.org).

[xvii] 1 John 1:3. 2 Peter 1:16. Acts 2:42.

[xviii] 1 Thessalonians 5:27. Colossians 4:16. Revelation 1:1. James 1:1. 1 Peter 1:1.

[xix] Geisler and Nix, 116-117.

[xx] Thiessen, Henry Clarence. Introduction to the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1948, 4th edition, 10.

[xxi] Geisler and Nix, 101.

[xxii] 2 Timothy 3:16. 2 Peter 1:20-21.

[xxiii] Rama, Shulchan Aruch, Even Ha’ezer 126:1.

[xxiv] Genesis 31:47. Jeremiah 10:11. Daniel 2:4-7:28. Ezra 4:8-6:18, 7:12-26.

[xxv] Mark 5:41, 7:34. Matthew 27:46. Romans 8:15. Galatians 4:6. 1 Corinthians 16:22.

[xxvi] Sir Frederick Kenyon. Source unknown.